Florida Social Contact Trends

Note: These are results of very preliminary work that has not been published and, therefore, subject to corrections. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation, other funding sources, or of the data vendor.

- DOI: Swaminathan, B., & Srinivasan, A. (2020, July 17). Social Contact Index.

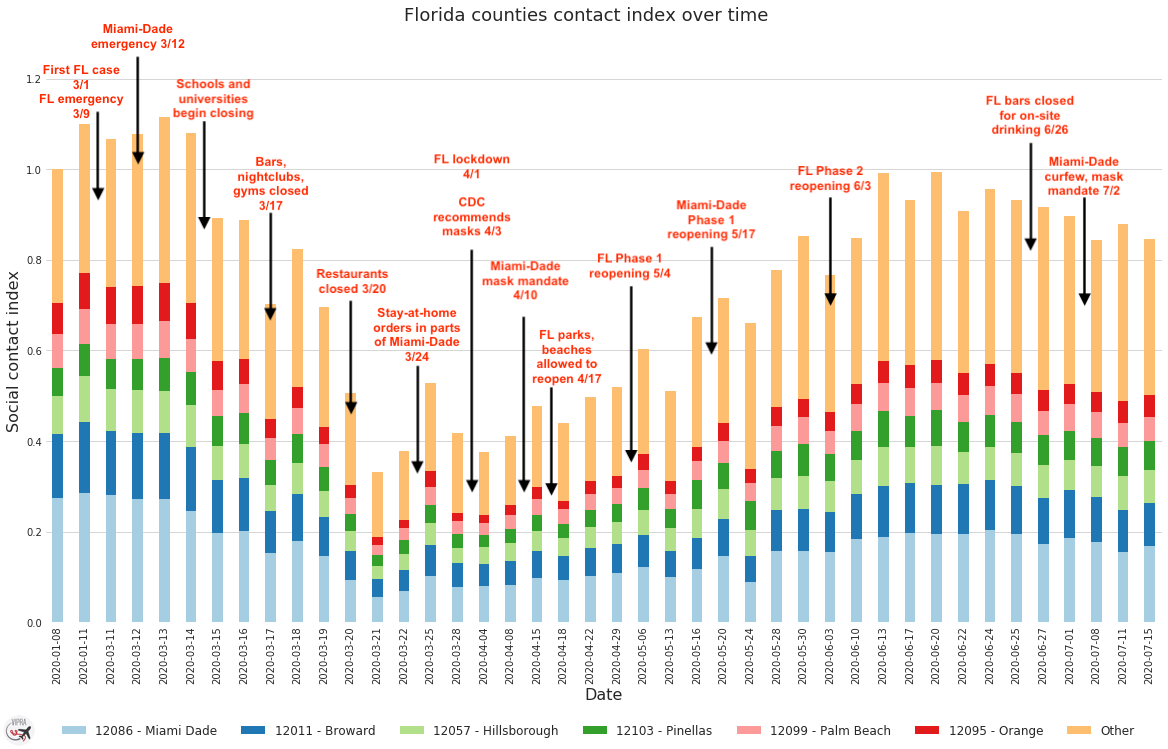

Impact of Government Policies on Social Contacts in Florida

Impact of government policies on social contacts in Florida.

Observations

- The state-level emergency declaration appears not to have affected social distancing.

- The beginning of school and university closures appears to have had a substantial impact on social distancing.

- Our data does not include schools, though.

- It is hard to say if the closure of bars, restaurants, etc. had an impact, or whether the subsequent social distancing was part of an earlier trend.

- Shelter-in-place did not impact social distancing. Social distancing had pretty much bottomed out by then.

- Florida’s reopening phases may not have had much of an impact on social distancing. Social contacts appear to have started rising even earlier. A significant increase in social contacts happened much after reopening, which suggests that social distancing fatigue might have been responsible for the rise in social contacts.

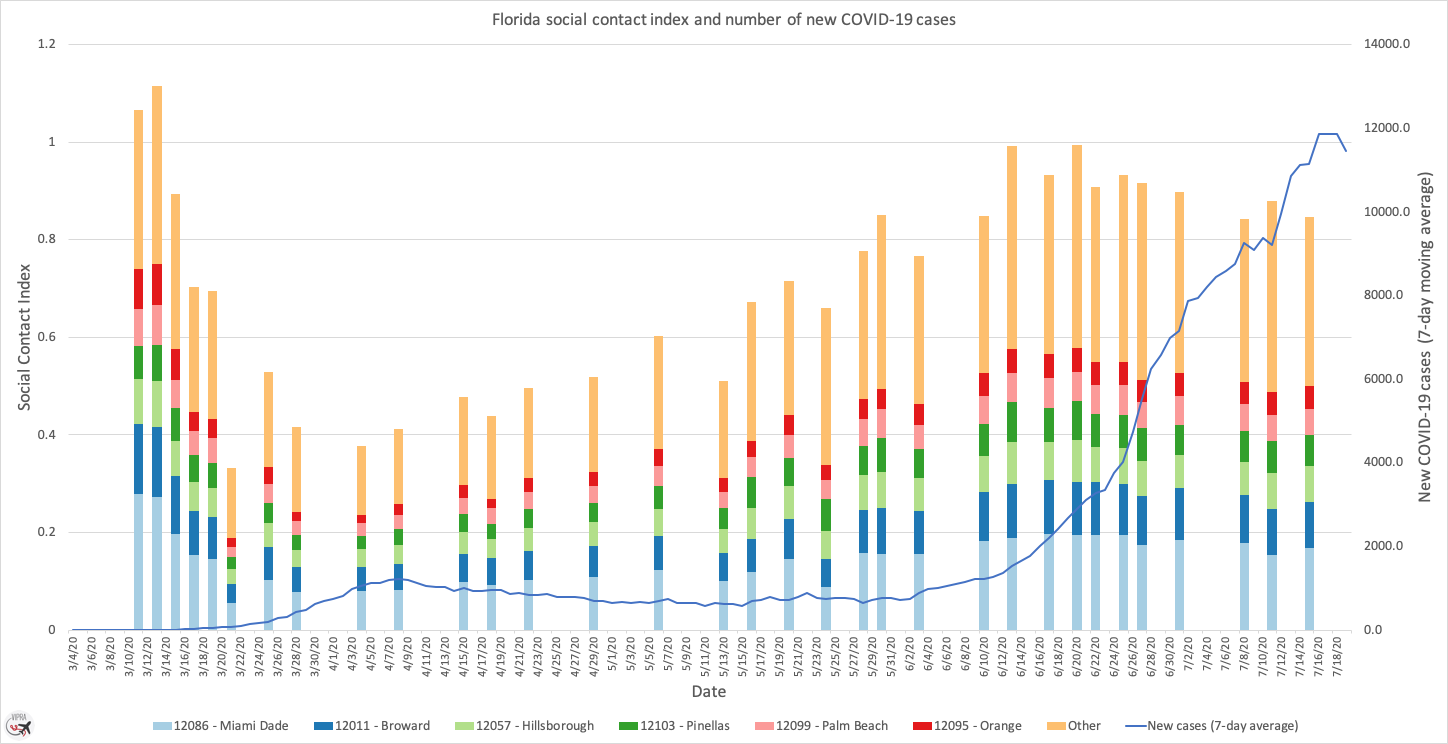

Social Contact Trends in Florida

Relationship of social contacts to COVID-19 case trends in Florida.

Observations

- The increase in COVID-19 cases toward the end of June was preceded by social contacts rising to close to the baseline trends in January.

- A sustained decrease in social contacts at the end of March to early April appears to have limited the number of COVID-19 cases in April.

- A moderate increase in social contacts in April-May did not lead to a rise in COVID-19 cases.

Summary of Preliminary Insights

- Human response to COVID-19 and events may play a more prominent role in impacting social contacts than government policy.

- Normal levels of social contacts appear to lead to a substantial spread of COVID-19.

- It may be possible to increase social contacts beyond the minimal level early in April while limiting COVID-19 spread.

Social Contacts Index

How we compute the social contact index

This work is based on Location Based Services (LBS) data. De-identified, privacy-enhanced data is provided by Cuebiq, which collects first party data anonymously from opted-in users who have provided informed consent through a GDPR and CCPA compliant framework.

We cluster data records from LBS to identify crowded places. We consider only data in certain permitted locations. We then estimate the density of people and then calculate the number of contacts generated by each cluster. In the analysis of Florida, we divide the total number of contacts across all clusters in Florida and divide by the number on January 8th to obtain the social contact index.

How we differ from other social distancing indices

- Many of the social distancing indices are based on human movement. But movement may not indicate contacts, and movement in rural areas may imply very different contact numbers than movement in urban areas.

- The CCI index from Cuebiq is most closely related to ours. We use data from Cueqbiq. However, Cuebiq computes its index directly from the proximity of records for different users. We estimate contacts after clustering and modeling to account for certain types of heterogeneity. For example, the number of records per user may vary so that a record may represent different amounts of time spent by people. The two approaches have different strengths and weaknesses.

Data sharing

Researchers may contact us for our fine-grained cluster data. We can provide cluster geo-coordinates and their normalized social contact indices.

Grants

- NSF RAPID grant on Leveraging New Data Sources to Analyze the Risk of COVID-19 in Crowded Locations. In collaboration with the CAM2 team at Purdue.

- NSF CSSI grant on Cyberinfrastructure for Pedestrian Dynamics-Based Analysis of Infection Propagation Through Air Travel.

- Supercomputing time on NERSC Cori, Argonne Theta, and TACC Frontera.

- This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or other funding sources.